A Handbook of Bandy; or, Hockey on the Ice/Chapter IV

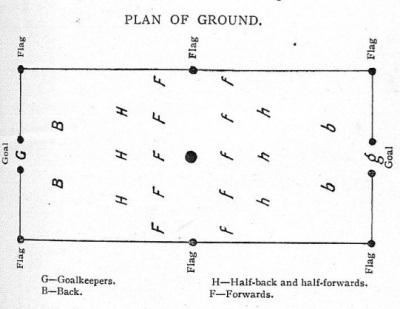

The players number eleven, divided as follows: - One goalkeeper, two backs, three half-backs, and five forwards (See plan of ground.)

As the object of the game is to obtain goals rather than prevent the opposing side from doing so, we will first consider the play of the forwards, the attacking force. These five players must act together, keeping about the same distance sideways from, and as a rule level with, each other; but when one of them is in possession of the ball the others may sometimes with advantage be a little in advance of him, provided they are not offside.

There will thus be one man in the centre of the field of play, with two players on each side of him, who are called “wing men,” the one nearest the side line being the outside wing, and the other the inside wing.

The play of the outside wing man should be near his side line, to prevent the ball, when passed to him, from going over the boundary line. Directly he has obtained the ball he should take it at full speed in the direction of his opponents’ goal line, still keeping near the side line, while at the same time he must keep a watch on his inside wing and centre forward. When within twenty or twenty-five yards of the goal line he should, the instant he sees a good opening, pass the ball (at right angles or slightly forward) to one of his companions. If for any reason he carries the ball within ten yards of the goal line, he should endeavour in pass the ball back to a point about fifteen yards in front of goal. This is hardly ever done, yet it is most important, and will often enable the centre forward to get a good shot for goal in spite of all the opposing backs can do, as when the ball is sent to him from in front it is much easier for him to obtain it than when it is hit to him from behind and has to be caught up. If on the other hand the wing man centres the ball by driving it forwards, it is almost certain to be met by one of the backs, who will promptly send it well down the ice. After having made his pass, the wing man should still keep somewhere near the side line, at about twenty-five yards from the goal line, unless the ball has been sent well behind him, when he must work his way back.

It will thus be seen an outside wing man has but little chance of getting goals himself, indeed, probably the better the game he plays the fewer goals will he score; he however, may be the means of many being obtained for his side. The inside wing, when he obtains the ball should at once make for goal, going as straight as possible. When he is likely to be tackled (as he is sure to be sooner or later) by the opposite halves, or full backs, he should get rid of the ball to the right or left, that is, to his centre or outside wing man. If he is a considerable distance from goal he should pass to his outside wing, but when getting towards the goal, the ball should be sent to the centre man. F, as is sometimes the case, he cannot pass to either, it is often right to send the ball right across to the wing players on the other side of the field.

As men are generally moving forward when a pass is made to a player, the ball should (unless you have time to see that he is standing still) be hit some distance in front of him. Sometimes, though very seldom, it is right for the inside wing, when he sees a fair opening, to make a dash for goal, with the object of getting a goal himself. It is impossible to say when this is right, but the general principle is sound that you should always pass when you see one of your own men in a better position for forwarding the attack than yourself, provided that you think you can hit the ball so that he will obtain it.

Now to turn to the centre man, on whom, to a great extent, it often depends what kind of game the forwards play. His most important duties are to feed his wings (that is, keep them supplied with the ball), and to be always level with whichever forward has the ball, until he is within fifteen yards of goal, where he should stop and wait for it to be centred to him from the wings; when he obtains the ball he should hit it hard and promptly straight between the goal posts, unless he elects to try and dodge the full back, and thus get a shot only opposed by the goalkeeper.

He should not advance much nearer to the goal, for as pointed out before, if the wing men carry the ball further up than this, they should centre back to about this point. The centre forward must play an unselfish game, not sticking to the ball and trying to make grand runs on his own account, but always on the lockout to see which of his wing men are in the best position to receive a pass; and directly he is hampered or tackled, away the ball should be sent to a wing forward, while he himself should make straight for goal as fast as his skates will carry him, always, of course provided he does not get offside.

Having now considered the play of the attacking part of the team, let us turn to those whose chief functions are defensive. The first line of defence is the three half backs (who might equally well be called half forwards), although their duties are mainly to provide the first line of defence, they must also aid the attack. As regards the attack no long description is necessary, for they have only to supply their forwards with the ball whenever they are in a position to do so, and to follow them down the field of play, ready to support them when for any reason they lose possession of the ball.

As regards the defence, their chief duty is to watch and tackle the opposing forwards; they should remember that there are five of these men to look after, and as they are only three in number, it is clear that each half-back cannot afford to devote himself entirely to one forward. The only method of forming a continuous line of defence is for each half to choose his position with reference to the game; and while adhering to it generally, he must rush now towards one forward, now towards the other, as the circumstances require. It will be obvious that one will play in the middle of the ground (who will be called the centre half), and the other two, one on each side.

The side halves must confine their attention to the forwards (outside and inside wing men) opposite to them. When either of these men have the ball, the half should bear in mind that at any time the player may get rid of it to one of his companions. When, therefore, he is tackling, or going to tackle, the man with the ball, he must be prepared to see the ball hit away out of his reach; it is possible, if he is very sharp and clever, he may see what the forward is going to do in time to intercept the pass, but this will not often be the case. When he is not successful in doing this he must at once go after the man to whom the ball has been sent.

As, however, the outside wing forward will rarely be able to get at the goal, or get a clear shot, and will be sure to be chiefly intent upon centring the ball, the half should be chary of rushing to the outside wing and losing all touch with the inside wing; It would usually be found best for him to be content with placing himself between the outside wing man and the goal with the object of stopping his shot at goal, or his pass to the centre. If, however, the forward tries to carry the ball on towards the goal, he must be tackled at once. Again, when the ball has been sent to one of the players on the other side of the ground, the half back must continue to watch his two wing men, always keeping between them and his own goal.

When the forward does not pass, but dribbles and dodges by the half, he must use every muscle to overtake him and prevent him getting a clear shot within striking distance of goal. Nothing is more vexing and disheartening for a player than to find that as often as he makes a dash for the man who has the ball it is quietly passed out of his reach to another opponent. The half may however remember for his consolation that if he has made the forward pass the ball he has done all that can fairly be expected of him for the time being.

So much for the wing-backs; a little more attention must be paid to the centre half-back, as his duties are somewhat different. The other two halves each have two wing men, but the cetre half has only the centre forward to look after, he, therefore, should and must give some help to his companions on the side he sees the attack is the most successful.

Also, when one of his brother halves has had to go right to the side lines, he may have to incline to that side, keeping a watchful eye upon the wing inside as well as upon the centre forward, and as the same time the half, on the other side of the field. When, however, the attack is being made near to goal, he should always keep an eye on the player who has the ball, for it is more than likely, sooner or later, the ball will be passed to that player.

If there is one forward who is known as a particularly dangerous man, the captain often tells one of his half-backs to pay especial attention to him, and he does this by shadowing him. It will be found that it is not of much use to shadow such as a player unless you keep very close to him; indeed, the closer you are the more likely you will be to hamper his play. Of course, no skater has the right to interfere with the movements of an opponent, so this must be avoided in shadowing a man.

The centre half, like the centre forward, must keep a keen look out on all the players, as he should be prepared to help and support any weak points in the defence, and he must also pass to whichever of his companions is in the best position for making use of the pass if he obtains the ball. It is so much easier to hit from right to left that often both the centre men (forward and half back) make all their passes to their left, while the right wing is left out in the cold, physically as well as metaphorically. This, of course, is not advisable, as it throws too much work on one wing and not enough on the other. It is, therefore, a good plan for both these centre men to make a practice, whenever they are not pressed, to see if it is not possible to pass to the right wing, especially as it is much easier for the right wing to centre when nearing goal line than for the left wing to do so.

When a strong attack is being made, the halves should often turn and skate homewards (never, however, so as to hamper their backs), keeping alongside the opposing forwards, whom they will more easily tackle in this way than by endeavouring to dash at them from in front. This arises from the ease with which a good dribbler can often dodge and pass an opponent who comes right at him, and the almost impossibility of the player who has been passed turning round and catching his man again.

A good deal of space has been occupied with the halves, but not more than the importance of their play requires. Unless these men play the correct game, the play of the forwards, however fine in itself, will be a failure; nor can the full backs successfully cope with even a weak attack, if the halves, instead of being in their proper places, are either half way down the field (when an attack is being made in their own half of the ground), or else right back in goal, getting in the way of the backs, and not leaving them full room to work.

On the other hand, with three good halves, even a weak set of forwards and backs will soon begin to play a correct game, for they are the connecting link between these two lines, and in the same way, as they work back towards goal, the backs must fall back with them.

We have now come to the second line of defence, or first line of pure defence, and this consists of the two full backs. These will act respectively as right and left back, and at the same time as an advance and rear back. They will be ready to rush and obtain the ball when it has been hit behind the halves, and also to rush forward and tackle any man who has got the ball past the halves and is about to make an unhampered shot for goal. If, however, he is quite on one side, and is hitting at a very small angle, they may find it better to stand in front of goal and stop the ball when it is hit. They must supply any weak place in the line of their halves, as, for instance, if the opposing forwards should have found a vacant place, and one of them is running through it with the ball, he must be met and tackled.

These duties will be undertaken equally by both the backs. At the same time they must in all cases, except when the attack is very close home, play as a forward (or advanced) back and a rear back, each one alternately going forward or dropping back, as the attack which he has to meet comes from his side or from the other. And as their chief function is defence – for they are the last protection of the goal except the goal-keeper – it is absolutely essential that the one who is for the time being acting as the rear back should not leave his post till the other has come to relieve him. Nothing should tempt him forwards, for the game is exceedingly fast (far more so than football or hockey), and he must be prepared at any minute for a fast forward of the hostile team dribbling by the halves, and coming down at full speed with the ball straight for goal. One situation, and one alone, may warrant him in leaving his post, namely, if he sees the ball hit to a place where he is sure he can reach it, and therefore get a clear hit before one of his opponents comes up.

In such a case, having reached the ball, he must hit it to the safest place he can chose, probably towards the side line; he must not attempt to pass it to a comrade where there is any risk of the pass not coming off; and he must regard any idea of making a run with the ball as little short of madness. To make a long dribble, dodging and skating by your perplexed opponents, to thread your way through your baffled enemies, is to the bandy player what a dashing innings is to a batsman at cricket; the prospect is almost intoxicating, and some men are never able to resist it, but such a man must not be a full back, nor, indeed, a half-back either. The back must think only of the safety of his goal, and, after having made his hit, he must hasten back to his place in the field, concerned lest he should have been too rash in ever having left it, rather than chafing at the pleasure he has just foregone.

The forward back may sometimes advance in touch with the halves a good way down the field of play, so as to give the halves on his side some support at a critical moment. This style of play has the advantage that it prevents a forward remaining near his (the back’s) goal, and waiting for a long forward pass being made to him, as with only the rear back and goalkeeper between him and the goal, he would be off side. If your opponents are very fast this is not a safe game to adopt, for a dribbler may break through the halves and go straight for goal with the ball, and if he gets any start upon the advanced back he will leave him hopelessly behind, and then may dodge the rear back, if the latter comes out to meet him; or if not, he will get close upon the goal, and be able to make his final hit with a fair chance of success.

The advanced back must, therefore, support the halves with great caution, and the instant he sees any likelihood of such a state of things arising as that just referred to, he must fly for goal with his utmost speed, happy if he can arrive in time to hamper or destroy the final shot. From this it will be seen that if a team is hard pressed they should seriously consider whether it is not wise to some extent to block their goal by keeping both backs in front of it. The disadvantage of doing this is that it enables the opposing forwards to keep between the halves and the goal, as they will be onside.

When the back gets a chance he should hit hard somewhat to the right or left, never, if he can help it, straight in front. If he is hard pressed and close to goal, he should hit direct to the side line, so as to clear the front of his goal. If there should be plenty of time, it may be well to hit for some point on the side line in the other half of the ground, as, if one of his forwards does not obtain the ball, and it goes outside, the game will have been transferred to the other half of the ice. It will be seen from these remarks that it is of great importance for the backs to know each other’s play, and play a combined game; for this reason it is advantageous to always have the same two men as backs.

We have now come to the last line of defence, the goalkeeper, who, if he is well up to his work, will stop many an otherwise winning hit, and the more the game has been played the greater has been the value placed upon this post. It was a frequent practice in former times to put the greatest duffer into goal, but this was a great mistake. The goal is like the keep of a fortress, and there of all places you must have a thoroughly reliable man; and so at bandy you must have between the goal posts a man of nerve, promptitude, resource, and experience; and as long as you have such a man, capable of dealing with each shot as it comes to hand, so long will all the well-managed dribbling, passing, and hitting of your opponents be of little use.

When the ball is hit along the ice the goalkeeper should, if he can, stop it with the side of his foot and skate, and not with his bandy, as the force of the ball will often brush the bandy away, and the ball will go over the goal line, or it may bound over the bandy with the same result. Still, if he cannot do this, and his bandy is the only thing that will reach the ball, he must of course use it; but whichever is used, foot or bandy, it should be placed at right angles to the direction in which the ball is coming, as otherwise it may be simply turned in its course, but not enough to prevent its passing between the goal posts. If, however, he has time, and the ball is coming direct to him, his safest plan is to pat his heels together and turn out his toes, and thus receive the ball. He should stand nearest to his left hand goal post, as, his bandy being in his right hand, he can cover more ice with it on the right than on the left.

When the goalkeeper has stopped the ball he should hit it away at once, and be sure that it goes well on the side, and never straight in front of goal; if he has not time to hit the ball, he should kick it away as far as possible. The most difficult shots to stop are not those which come along the ice, but which are hit upwards from the ice, and come in the air or bounce near the goal. The problem of stopping these is not an easy one; it is almost hopeless to make the attempt with the bandy, but by trying to catch the ball with his hand or placing his body in the way he may manage to stop the ball, particularly if he is a fairly good fielder at cricket.

Having now to some extent indicated the way to play the game, it may be as well to consider how a captain of a team should choose his men for the various places in the field. The outside wing men should be your fast men who are not clever dribblers, as they will generally have a clear run. The inside wing must be good dribblers, and also good shots at goal and fairly fast. The centre forward should be the cleverest forward on his side; he must be a cool, clear-headed player, a quick and accurate shot at goal, and as unselfish as it is possible to be. If he has all these qualities he need not be a very fast skater, although pace is a great advantage.

The three half-backs should be the hardest workers on the side and those that tire least; they must be fast for a short distance, the centre half should be the best man of the three. The two backs need not be fast skaters, but should be quick, active, and very firm on their skates; they must also be the surest hitters and safest tacklers of the team; and, above all, men of judgment and experience. Big men are better than small men, other things being equal. The goalkeeper should also be a safe hitter, active and firm on his skates; he need not be a good skater nor tackler. Perhaps it may be added he should be the warmest-blooded Johnnie of the lot, for all the other ten men will, or at any rate should, keep warm, but the goalkeeper is bound to have a cold job, although he may have what is called a warm time of it every now and then. The best position in the field from which to captain a team is the centre half-back; if this place does not suit, one of the backs, or else centre forward, are next best positions.